Thinking, Fast and Slow.

A tribute to Daniel Kahneman

Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize-winning psychologist, revolutionized our understanding of judgment and decision-making.

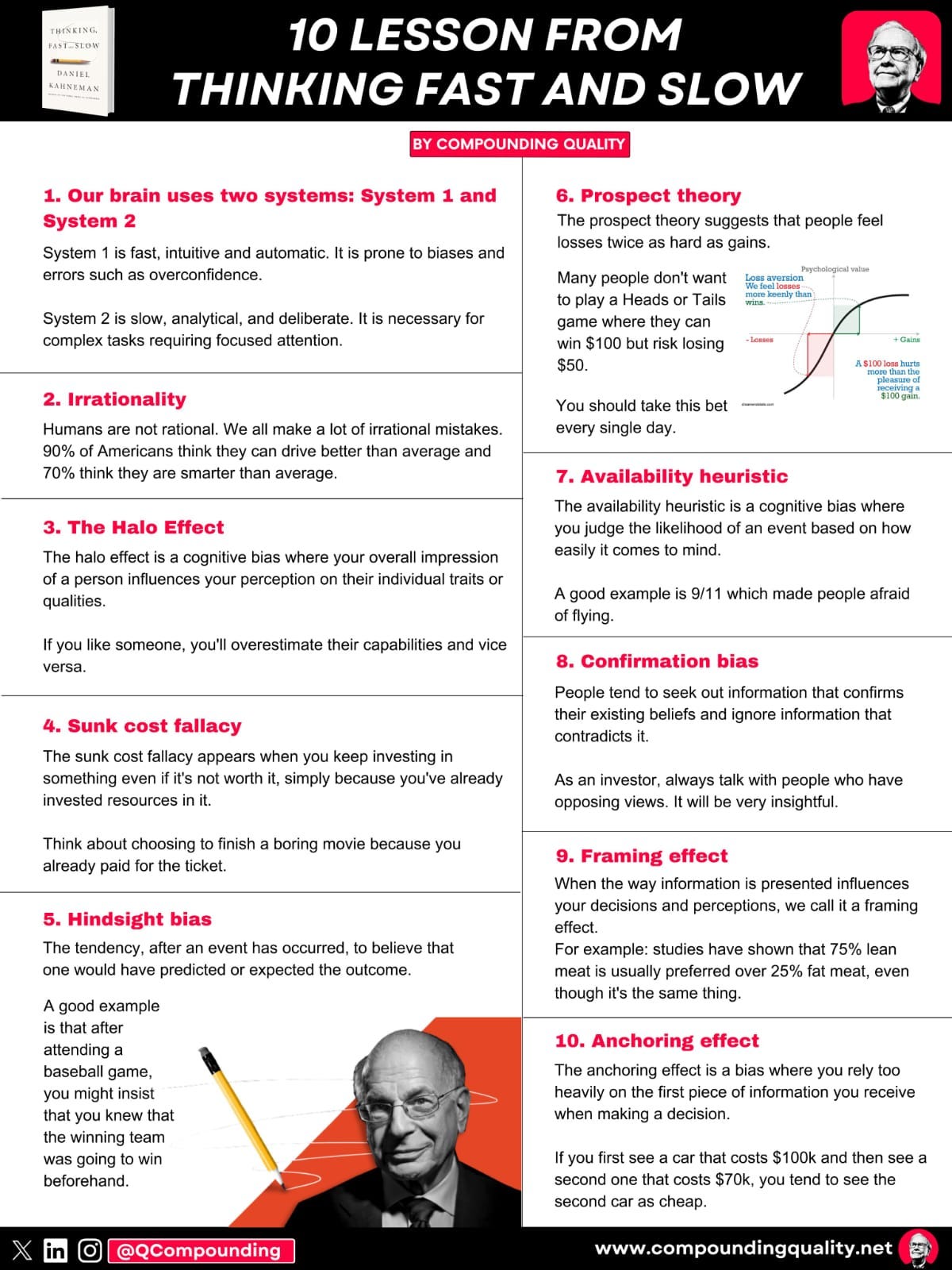

In his landmark book, "Thinking, Fast and Slow," he draws back the curtain on the two systems that drive our thinking. System 1 is our fast, intuitive, and automatic mode, while System 2 is slow, deliberate, and effortful.

Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.

Kahneman's decades of research, conducted alongside his collaborator Amos Tversky, forever altered the field of economics.

They challenged the notion of humans as purely rational actors, instead highlighting the biases and mental shortcuts that frequently sway our decisions - an idea that defines pretty much why people do what they do (inspite of them saying something else)

"Intelligence is not only the ability to reason; it is also the ability to find relevant material in memory and to deploy attention when needed."

His work led to more conversations around behavioral economics, a revolutionary field that merges the insights of psychology with the rigor of economic analysis.

He died recently and today’s newsletter is a tribute to his work.

The Two Systems

Our minds operate using two distinct systems.

System 1 is fast, intuitive, automatic, and largely unconscious. It effortlessly generates impressions, feelings, and inclinations.

System 2 is slow, deliberative, conscious, and effortful. It is responsible for reason and self-control.

Heuristics: Mental Shortcuts

This is the essence of intuitive heuristics: when faced with a difficult question, we often answer an easier one instead, usually without noticing the substitution.

Because System 2 is slow and effortful, we often rely on System 1's simpler approach in making judgments.

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that substitute a simpler question for a more difficult one. They are designed to deliver quick, intuitive answers – but not always accurate ones.

The Availability Heuristic

We judge the frequency or likelihood of events by how readily examples come to mind. This means events that are vivid, recent, or emotionally charged will skew our perceptions.

Anchoring

Our judgments often start with a reference point or "anchor," and then adjust from there. These anchors can be completely arbitrary, yet still influence our thinking.

The Halo Effect

When we form an overall impression of an individual or situation, we tend to extend our feelings about one aspect to other unrelated aspects.

Overconfidence

We are prone to be overly confident in our own judgments and skills. This arises because we focus on what we know and neglect what we don't. The very fact we can construct a narrative can give us an illusion of understanding.

Loss Aversion

Losses hurt roughly twice as much as gains feel good. The pain of losing $100 is more powerful than the joy of winning $100. This asymmetry influences many of our decisions, from the stock market to making deals.

Framing Effects

The way choices or information are presented to us dramatically influences how we perceive them.

The Peak-End Rule

We don't judge our experiences by their total amount of pain or pleasure. Instead, they are strongly influenced by the peaks (best or worst moments) and how they ended.

Two Selves: Experiencing and Remembering

Our minds work like two selves: The experiencing self lives in the moment, sensing the world and feeling emotions. The remembering self keeps score, holds the story of our lives, and makes the choices that matter most. Unfortunately, these two selves don't always agree on what made us happy.